In the realm of occupational health and safety, risk management plays a crucial role in safeguarding lives, assets, and the environment. A fundamental concept that underpins effective risk control strategies is the ALARP principle, which stands for “As Low As Reasonably Practicable.” This principle guides decision-makers in balancing safety improvements with practicality and cost-effectiveness. But beyond its textbook definition, ALARP represents a mindset—a continuous commitment to minimizing harm proportionately and responsibly.

What Is the ALARP Principle?

The ALARP principle is a core concept in health and safety management that refers to reducing risks to a level that is “as low as reasonably practicable.” This means employers are not obligated to eliminate all risk—an impossible task—but must reduce it to a level where further risk reduction would involve costs (in terms of money, time, or effort) that are grossly disproportionate to the benefit gained.

According to the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the term “reasonably practicable” involves weighing a risk against the trouble, time, and money needed to control it. If these are grossly disproportionate to the risk reduction achieved, the action may not be required. However, where a risk is significant, stronger justifications are needed for not implementing a measure.

The Legal and Ethical Significance of ALARP

1. Legal Responsibility

The ALARP concept is embedded in many national and international safety laws, especially in high-risk industries such as construction, oil and gas, chemical processing, and nuclear power. For instance, in the UK, the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 obliges employers to ensure the health and safety of workers and others “so far as is reasonably practicable.”

Failure to adhere to ALARP can expose an organization to regulatory penalties, lawsuits, and reputational damage. Courts and inspectors may use the ALARP test to assess whether a company did enough to manage a known risk.

2. Ethical and Moral Accountability

Beyond legal compliance, ALARP reflects an ethical commitment to value human life and well-being. By ensuring risks are minimized in a balanced way, employers uphold their moral responsibility to protect workers, customers, and the public.

ALARP in Practice: How It Works

Step 1: Risk Assessment – The Foundation of ALARP

Risk assessment is the first and most critical step in applying the ALARP principle. It involves systematically identifying workplace hazards and evaluating their associated risks based on likelihood and severity. This process is not just a legal requirement—it provides the foundation for making rational, evidence-based safety decisions.

Practical Implementation:

Start by walking through your workplace or site and listing all the tasks performed. Use structured checklists, safety inspection forms, and input from employees who perform the tasks daily. Consider all sources of harm—mechanical, chemical, electrical, ergonomic, environmental, and psychosocial.

Then, use a risk matrix to assign scores to each identified hazard. This matrix typically rates the likelihood (rare to almost certain) and consequence (minor injury to fatality). For example, a rotating machinery hazard with a high chance of entanglement and severe injury might score as “High Risk.”

Involve employees and supervisors during this phase. Workers often know the practical issues and “near-miss” scenarios that might not be in official logs. Also, include temporary workers or contractors in your assessment to avoid blind spots.

By documenting each hazard, its risk rating, and the existing controls, you create a baseline that allows you to compare whether further risk reductions are reasonably practicable later in the process.

Key Tip: Use simple digital tools like Microsoft Excel or cloud-based apps such as iAuditor or Safetymint to standardize and store your risk assessments for review, updates, and compliance.

Step 2: Evaluate Control Measures – Applying the Hierarchy of Controls

Once hazards have been identified and their risk levels assessed, the next step is to determine appropriate control measures. This is where the Hierarchy of Controls comes in—a structured approach to prioritizing how risks should be managed, ranked from most to least effective.

Practical Implementation:

The hierarchy includes:

-

Elimination – Remove the hazard entirely.

-

Substitution – Replace it with something safer.

-

Engineering Controls – Isolate people from the hazard.

-

Administrative Controls – Change how people work.

-

PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) – Protect the worker.

Let’s use an example: Suppose workers are exposed to harmful dust during cutting operations. The first question is, can you eliminate the dust? If not, can the cutting process be substituted with a less dusty method, such as wet cutting? If that’s not feasible, consider engineering controls like local exhaust ventilation.

The goal is to push control efforts toward the top of the hierarchy, where the measures are more effective and less reliant on human behavior. Only after exhausting options at higher levels should you consider PPE and procedural controls.

Key Tip: Don’t just rely on PPE as the default—it’s the least effective measure. Always justify why higher-level controls are not feasible. Document every consideration and include cost-benefit data to show that your selected measures are both effective and reasonably practicable.

Step 3: Cost-Benefit Analysis – Judging Reasonable Practicability

This step is the heart of the ALARP principle. It asks: Is the cost, time, or effort required to implement a further risk control grossly disproportionate to the benefit gained? This isn’t about avoiding costs—it’s about justifying decisions logically and ethically.

Practical Implementation:

To perform a basic cost-benefit analysis, begin by estimating:

-

The risk reduction benefit: What are you achieving by implementing the measure? For instance, are you reducing a “high” risk to “low”? Are you preventing a serious injury or just a minor inconvenience?

-

The cost and feasibility: How much money, time, or operational change would the control require? Would implementing it introduce new hazards?

For example, if installing an automatic shutdown system costs $20,000 and prevents a rare but potentially fatal incident, it might be reasonably practicable. But if a $500,000 measure only reduces a trivial risk from “low” to “very low,” and introduces downtime or complexity, it may be grossly disproportionate.

Use documented figures (e.g., vendor quotes, incident costs, downtime estimates) and, where available, industry benchmarks for risk valuations.

Key Tip: When in doubt, lean toward safety. In most jurisdictions, especially under UK law, if a risk could cause serious injury or death, higher spending may be justified. Keep a transparent record of how you reached your decision.

Step 4: Document Justifications – Creating a Defensible Record

Documentation is critical in the ALARP process. You must be able to prove, if challenged, that you identified risks, considered appropriate controls, and made decisions based on a sound cost-benefit rationale. Regulators, insurers, or even internal auditors will look for this trail if something goes wrong.

Practical Implementation:

For each hazard and control considered, create a Risk Reduction Justification Sheet (a simple template works well). Include:

-

The nature of the hazard

-

Initial risk rating

-

Control measures considered

-

Those implemented (with justification)

-

Those rejected (with the reason why they were not reasonably practicable)

-

Cost estimates or operational challenges (where applicable)

-

Final residual risk rating

Back this up with supporting documents such as supplier quotes, safety data sheets, product specifications, meeting minutes, and photographs. Digital tools like SharePoint, Google Drive, or a simple cloud-based safety management system can help organize these files for accessibility and future reference.

Key Tip: During inspections or after incidents, regulators often ask: Why didn’t you implement this control? A documented, reasoned answer is your best defense. “We thought it was too expensive” is not good enough—show your ALARP reasoning.

Step 5: Review and Improve – ALARP Is a Continuous Process

The final step is to recognize that ALARP is not a one-off exercise. Workplace conditions, technologies, workforce skills, and regulations evolve. What was once not reasonably practicable might become feasible over time due to reduced costs, better methods, or new evidence.

Practical Implementation:

Set a schedule to review your risk assessments and controls periodically—at least annually or after any major changes, such as:

-

Introduction of new equipment

-

Changes in work procedures

-

A serious incident or near miss

-

Regulatory updates or enforcement trends

Use these reviews to ask: Can we do better now than we could before?

Encourage employee feedback. Toolbox talks and safety meetings are great opportunities to gather frontline insights. Ask: Are the controls working? Have new risks emerged? Is the training effective?

Keep an eye on innovations in your industry. For example, if a new type of guarding system becomes affordable and easy to install, what was previously not reasonably practicable might now meet the ALARP threshold.

Read Also: 5 Key Elements of the Risk Management Process

Limitations of ALARP

The major limitation in this analysis is that risk and sacrifice are not usually measured in the same units, so it’s a bit like comparing two very different things, e.g., apples and pears.

The proposed solution to this limitation is to adopt the CBA (Cost-Benefit Analysis). In CBA, both risk and sacrifice are converted to a common set of units – MONEY, making it possible for them to be compared.

The carrot diagram

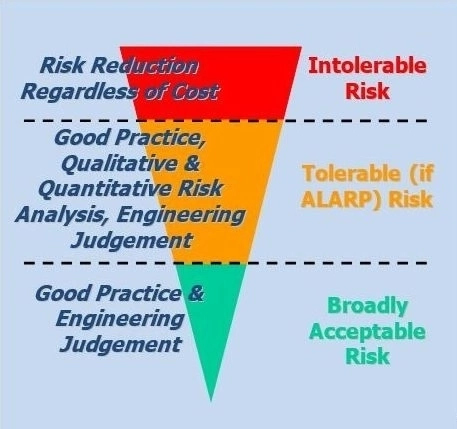

The carrot diagram is used to explain “as low as reasonably practicable”. It has a wider top part termed – unacceptable region and a thin base termed – acceptable region.

The region is in-between the top and base and is mostly recognized as the “as low as reasonably practicable region.

This expression has been said to be misleading since there is no legal requirement for risks to be tolerable, nor any recognition that low risks may be regarded as broadly acceptable.

However, to determine what is tolerable/acceptable, duty holders (Policy makers and those engaged in program delivery, Enforcers, and Technical specialists) must exercise judgment, referring to existing good practices that have been established by a process of discussion with stakeholders to achieve a consensus about what is ALARP.

The Human Element in ALARP

A unique, often under-discussed aspect of the ALARP principle lies in its subjectivity—what is “reasonably practicable” can vary depending on context, culture, and individual judgment. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity.

Challenge: Two safety managers in different organizations may arrive at different conclusions about what is practicable, based on budget constraints, technological access, or operational culture.

Opportunity: Organizations can use this subjectivity to promote proactive safety cultures. Rather than doing the bare minimum, businesses that go beyond legal compliance and embrace the spirit of ALARP often see better employee engagement, improved productivity, and lower long-term costs.

Research by Hale et al. (2007) notes that companies with strong safety cultures tend to use ALARP as a dynamic concept, integrating it into their operational decision-making rather than treating it as a checklist item.

Real-World Example: ALARP in the Construction Industry

Consider a construction site where workers are exposed to the risk of falling from heights. Installing guardrails, safety nets, and providing fall arrest harnesses may involve substantial cost. However, if the risk of a fall could result in serious injury or death, the investment is not grossly disproportionate to the benefit.

Failing to implement these measures would not satisfy the ALARP principle. In this case, the control measures are reasonably practicable, and their implementation is not just good practice—it’s a legal and moral obligation.

Conclusion

The ALARP principle remains highly relevant as industries embrace innovation, automation, and remote work technologies. As new risks emerge—from artificial intelligence to climate-related hazards—the need for a robust, principle-based risk management framework like ALARP becomes even more critical.

By understanding and applying ALARP thoughtfully, health and safety professionals not only comply with the law but also cultivate trust, uphold ethical standards, and protect what matters most—human life.

References:

-

HSE (2022). Reducing risks, protecting people: ALARP at a glance.

-

Hale, A. R., Borys, D., & Else, D. (2007). Management of safety: The role of ALARP in risk assessment and decision-making. Journal of Safety Research.

Related Posts

Hierarchy Of Control: 5 Clear Levels of Risk Control

The Importance of Safety in the Manufacturing Industry

Occupational Exposure: Examples And OEL

A seasoned Health and Safety Consultant with over a decade of hands-on experience in Occupational Health and Safety, UBONG EDET brings unmatched expertise in health and safety management, hazard prevention, emergency response planning, and workplace risk control. With a strong passion for training and coaching, he has empowered professionals and organizations to build safer, more compliant work environments.

Certified in globally recognized programs including NEBOSH, ISO standards, and OSHA regulations, he combines technical know-how with practical strategies to drive health and safety excellence across industries. designing comprehensive HSE management systems or delivering impactful safety training, whether he] is committed to promoting a culture of safety and continuous improvement.